The Philadelphia Convention

In May 1787, fifty-five delegates arrived in Philadelphia. They came from every state except Rhode Island, where the legislature opposed increasing central authority. Most were strong nationalists; forty-two had served in the Confederation Congress. They were also educated and propertied: merchants, slaveholding planters, and “monied men.” There were no artisans, backcountry settlers, or tenants, and only a single yeoman farmer.

Some influential Patriots missed the convention. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were serving as American ministers to Britain and France, respectively. The Massachusetts General Court rejected Sam Adams as a delegate because he opposed a stronger national government, and his fellow firebrand from Virginia, Patrick Henry, refused to attend because he “smelt a rat.”

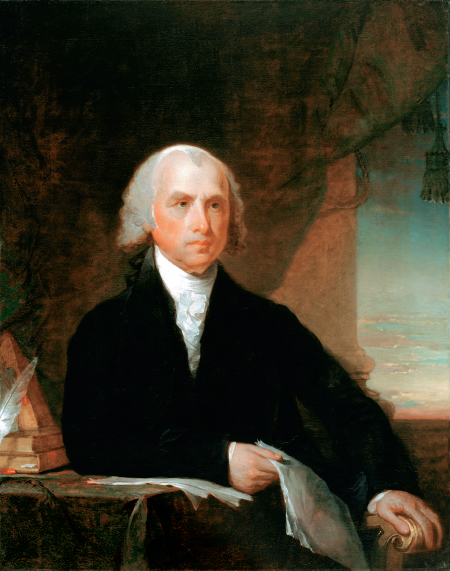

The absence of experienced leaders and contrary-minded delegates allowed capable younger nationalists to set the agenda. Declaring that the convention would “decide for ever the fate of Republican Government,” James Madison insisted on increased national authority. Alexander Hamilton of New York likewise demanded a strong central government to protect the republic from “the imprudence of democracy.”

The Virginia and New Jersey Plans The delegates elected George Washington as their presiding officer and voted to meet behind closed doors. Then — momentously — they decided not to revise the Articles of Confederation but rather to consider the so-called Virginia Plan, a scheme for a powerful national government devised by James Madison. Just thirty-six years old, Madison was determined to fashion national political institutions run by men of high character. A graduate of Princeton, he had read classical and modern political theory and served in both the Confederation Congress and the Virginia assembly. Once an optimistic Patriot, Madison had grown discouraged because of the “narrow ambition” and outlook of state legislators.

Madison’s Virginia Plan differed from the Articles of Confederation in three crucial respects. First, the plan rejected state sovereignty in favor of the “supremacy of national authority,” including the power to overturn state laws. Second, it called for the national government to be established by the people (not the states) and for national laws to operate directly on citizens of the various states. Third, the plan proposed a three-tier election system in which ordinary voters would elect only the lower house of the national legislature. This lower house would then select the upper house, and both houses would appoint the executive and judiciary.

From a political perspective, Madison’s plan had two fatal flaws. First, most state politicians and citizens resolutely opposed allowing the national government to veto state laws. Second, the plan based representation in the lower house on population; this provision, a Delaware delegate warned, would allow the populous states to “crush the small ones whenever they stand in the way of their ambitious or interested views.”

So delegates from Delaware and other small states rallied behind a plan devised by William Paterson of New Jersey. The New Jersey Plan gave the Confederation the power to raise revenue, control commerce, and make binding requisitions on the states. But it preserved the states’ control of their own laws and guaranteed their equality: as in the Confederation Congress, each state would have one vote in a unicameral legislature. Delegates from the more populous states vigorously opposed this provision. After a month-long debate on the two plans, a bare majority of the states agreed to use Madison’s Virginia Plan as the basis of discussion.

This decision raised the odds that the convention would create a more powerful national government. Outraged by this prospect, two New York delegates, Robert Yates and John Lansing, accused their colleagues of exceeding their mandate to revise the Articles and left the convention. The remaining delegates met six days a week during the summer of 1787, debating both high principles and practical details. Experienced politicians, they looked for a plan that would be acceptable to most citizens and existing political interests. Pierce Butler of South Carolina invoked a classical Greek precedent: “We must follow the example of Solon, who gave the Athenians not the best government he could devise but the best they would receive.”

The Great Compromise As the convention grappled with the central problem of the representation of large and small states, the Connecticut delegates suggested a possible solution. They proposed that the national legislature’s upper chamber (the Senate) have two members from each state, while seats in the lower chamber (the House of Representatives) be apportioned by population (determined every ten years by a national census). After bitter debate, delegates from the populous states reluctantly accepted this “Great Compromise.”

Other state-related issues were quickly settled by restricting (or leaving ambiguous) the extent of central authority. Some delegates opposed a national system of courts, predicting that “the states will revolt at such encroachments” on their judicial authority. This danger led the convention to vest the judicial power “in one supreme Court” and allow the new national legislature to decide whether to establish lower courts within the states. The convention also refused to set a property requirement for voting in national elections. “Eight or nine states have extended the right of suffrage beyond the freeholders,” George Mason of Virginia pointed out. “What will people there say if they should be disfranchised?” Finally, the convention specified that state legislatures would elect members of the upper house, or Senate, and the states would select the electors who would choose the president. By allowing states to have important roles in the new constitutional system, the delegates hoped that their citizens would accept limits on state sovereignty.

Negotiations over Slavery The shadow of slavery hovered over many debates, and Gouverneur Morris of New York brought it into view. To safeguard property rights, Morris wanted life terms for senators, a property qualification for voting in national elections, and a strong president with veto power. Nonetheless, he rejected the legitimacy of two traditional types of property: the feudal dues claimed by aristocratic landowners and the ownership of slaves. An advocate of free markets and personal liberty, Morris condemned slavery as “a nefarious institution.”

Many slave-owning delegates from the Chesapeake region, including Madison and George Mason, recognized that slavery contradicted republican principles and hoped for its eventual demise. They supported an end to American participation in the Atlantic slave trade, a proposal the South Carolina and Georgia delegates angrily rejected. Unless the importation of African slaves continued, these rice planters and merchants declared, their states “shall not be parties to the Union.” At their insistence, the convention denied Congress the power to regulate immigration — and so the slave trade — until 1808 (American Voices).

The delegates devised other slavery-related compromises. To mollify southern planters, they wrote a “fugitive clause” that allowed masters to reclaim enslaved blacks (or white indentured servants) who fled to other states. But in acknowledgment of the antislavery sentiments of Morris and other northerners, the delegates excluded the words slavery and slave from the Constitution; it spoke only of citizens and “all other Persons.” Because slaves lacked the vote, antislavery delegates wanted their census numbers excluded when apportioning seats in Congress. Southerners — ironically, given that they considered slaves property — demanded that slaves be counted in the census the same as full citizens, to increase the South’s representation. Ultimately, the delegates agreed that each slave would count as three-fifths of a free person for purposes of representation and taxation, a compromise that helped southern planters dominate the national government until 1860.

National Authority Having addressed the concerns of small states and slave states, the convention created a powerful national government. The Constitution declared that congressional legislation was the “supreme” law of the land. It gave the new government the power to tax, raise an army and a navy, and regulate foreign and interstate commerce, with the authority to make all laws “necessary and proper” to implement those and other provisions. To assist creditors and establish the new government’s fiscal integrity, the Constitution required the United States to honor the existing national debt and prohibited the states from issuing paper money or enacting “any Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.”

The proposed constitution was not a “perfect production,” Benjamin Franklin admitted, as he urged the delegates to sign it in September 1787. But the great statesman confessed his astonishment at finding “this system approaching so near to perfection.” His colleagues apparently agreed; all but three signed the document.